Hill of the Buddha

Imagine walking through a dark tunnel, then stepping into light to find a massive Buddha’s face staring down at you from a dome open to the sky—this is the Hill of the Buddha in Sapporo.

If you walk through the Makomanai Takino Cemetery in the hills south of Sapporo, Hokkaido, you’ll notice something unusual. This is Japan’s largest private cemetery, spreading across 180 hectares, but it doesn’t look like a typical burial ground. There are 33 Moai statues standing here, a large stone replica of Stonehenge, and tucked among them is something even more striking—the Hill of the Buddha, designed by world-renowned architect Tadao Ando and completed in December 2015.

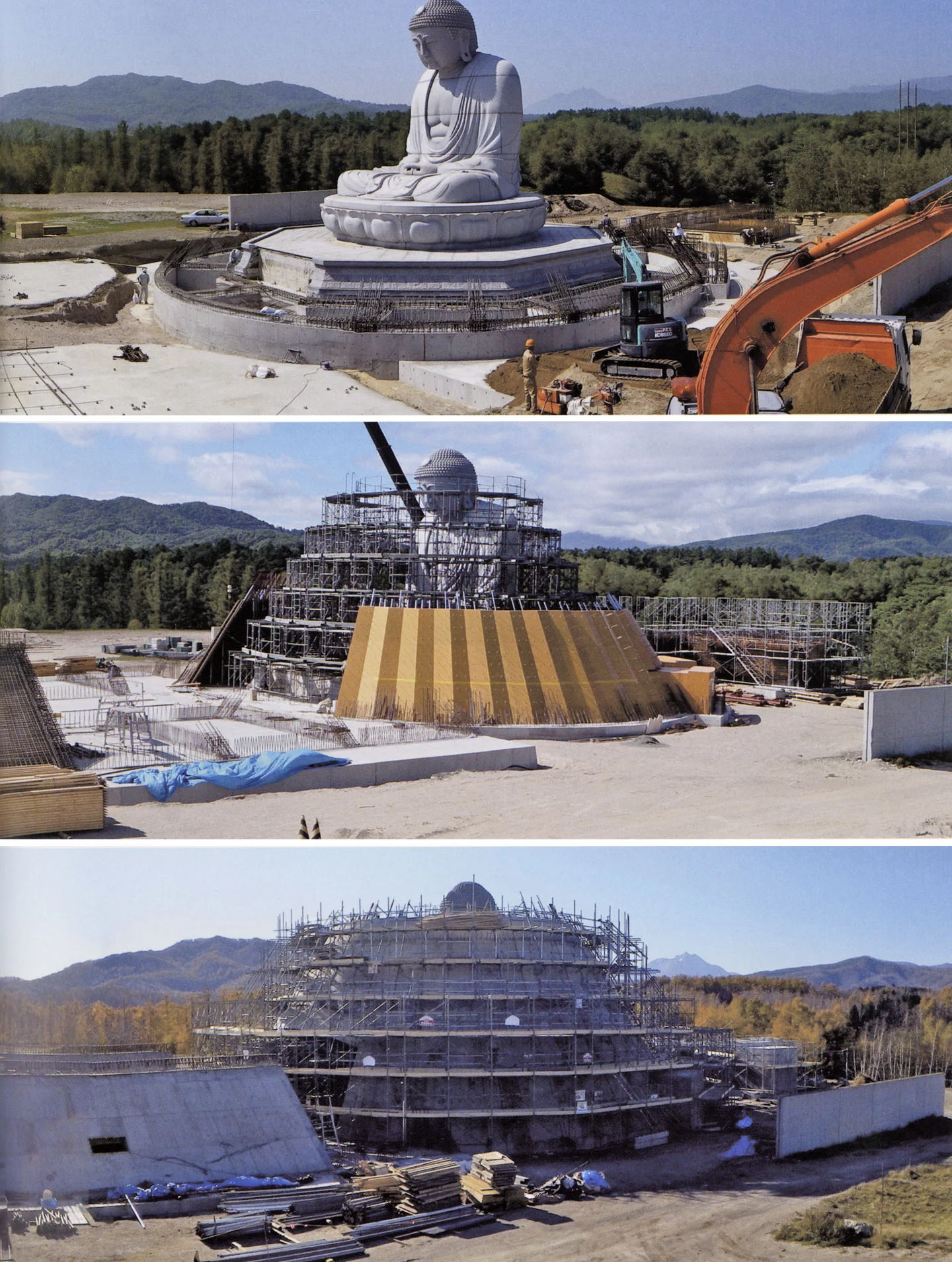

The story begins with a large stone Buddha that was carved on this spot around the year 2000. The statue stands 13.5 meters tall and weighs 1,500 tons, carved from 4,000 tons of raw stone. The craftsmanship is impressive—a perfectly cut head, carefully polished stone that shows off its natural grain. But for 15 years, the statue just stood there alone, out in the open, surrounded by empty landscape. Despite its size and beauty, it seemed awkwardly placed, lacking the presence that a monument like this deserved.

The cemetery’s chairman, Yukio Takahashi, saw the problem. He approached architect Tadao Ando and asked him how they could make the Buddha “a more spiritually moving existence.” Ando thought about the ancient sacred spaces he’d studied—the rock-cut temples of Ajanta in India, and the cave sanctuaries carved into Chinese mountains. Those places created something powerful through enclosure, through the way light filtered through stone. His proposal was simple and radical: “Let’s bury it!” His idea was to cover the entire statue with a man-made hill planted with lavender, leaving just the top of the Buddha’s head visible above the mound.

The design became known as Atama Daibutsu, or “Large Buddha’s Head.” Instead of a monument you look at from a distance, Ando created something you discover. The approach feels almost ceremonial. From far away, at first, you only catch a glimpse of the Buddha’s head rising above a lavender-covered hill. As you walk closer along the straight path, the head disappears. The path takes you around a water court, a reflecting pool surrounded by concrete walls, serving as a sacred threshold that marks the transition between the realms of the sacred and worldly. The path from the pool then leads you into a tunnel corridor. Ando calls it a “womb space”—enclosed, quiet. The further you walk, the more the outside world fades away until there’s only silence.

After about forty meters, the tunnel opens up. You step into a circular space enclosed by concrete walls, and the secluded Buddha appears, fully visible for the first time. You look up and see its face framed by an opening to the sky, natural light falling directly onto the stone. Standing there, you don’t feel overwhelmed or awestruck the way big monuments usually make you feel. You feel quiet and calm. It’s a rare kind of peace.

This journey, from darkness into light, from a dark tunnel into open space, feels intentional but not forced. The dome stays open to the weather. Rain falls in, snow piles up in winter, wind moves through.

Building the lavender hill was a massive undertaking on its own. It needed 150,000 lavender plants, and sourcing such a large quantity proved difficult. Workers had to secure nursery stock bit by bit and take care of the plants before they could even start planting. Local residents volunteered to help, turning this project into a community effort. Now the hill transforms throughout the year. In summer, when the lavender blooms, the hill becomes a sea of purple surrounding the stone head. In autumn, the colors fade to muted browns and greens. Winter transforms everything; the mound disappears under snow, and the Buddha’s head rises from a field of white. The colors keep changing with Hokkaido’s seasons, giving the monument a different face each time you visit.

The construction itself, which started in May 2014, was as ambitious as the idea. The original Buddha was left untouched and workers had to be extremely careful not to damage it. Everything else, the concrete shell and the shaped landscape, was built around it. Ando worked with Otata Construction, a company known for its precise concrete work, to create the perfect curve of the tunnel and the circular courtyard inside the mound. The project opened in December 2015. It was a collaboration of vision and discipline between Ando’s architectural concept, Takahashi’s courage to take the risk, and the craftsmen who realized it.

What makes the Hill of the Buddha particularly striking is how it changes your relationship with the monument itself. Such large religious statues are typically meant to be seen, often placed in prominent positions. Ando did the opposite. By burying the Buddha, he made it something you have to seek out, something you earn through the journey. He once said he wanted to make the Buddha “a presence that touches people’s hearts.” In the hills of Hokkaido, he did exactly that.

![[Photos] Autumn Colors at Kotokuji Temple](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fsgp1.vultrobjects.com%2Fpfj-static%2F2025%2F11%2FIutHLn2g-02.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![[Site Update] Goshuin Collection](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fsgp1.vultrobjects.com%2Fpfj-static%2F2025%2F11%2FIMG_3251.webp&w=3840&q=75)