Old colonial-style house has been sitting in Tokyo for almost 140 years

Let’s explore one of the oldest Western-style residential buildings in Tokyo that still exist.

We are in a quiet residential neighborhood in Uguisudani in Tokyo’s Taito ward. On this unlikely spot surrounded by mostly new houses, there is one building in front of us that sticks out. Visibly run-down, it’s a wooden house in colonial style that would be more commonly found on the east coast of the United States rather than Japan. Large part of its exterior is covered in bright green ivy. How much more charming can this get?

This fine house is considered to be one of the oldest existing Western-style residential buildings in Tokyo. But compared to a standard colonial house, it’s a little bit unusual — there are large glass windows spanning across most the front side on both first and second floors. The whole exterior, except for the roof, is painted in white. Pine tree wood from America was used for construction.

At first glance, the house does look abandoned, but in fact it’s a private residence and people live here. So unfortunately, we need to stay behind the fence to avoid trespassing.

Research reveals that on the first floor, there are drawing and study rooms. Each room is equipped with a fireplace. The second floor with the balcony has a large room the size of 20 tatami mats. On the wall, there is a huge mirror about 5 meters wide and 2 meters high. It is said that often foreign diplomats were invited here, and parties were held.

Foreign diplomats? Parties? Who lived here?

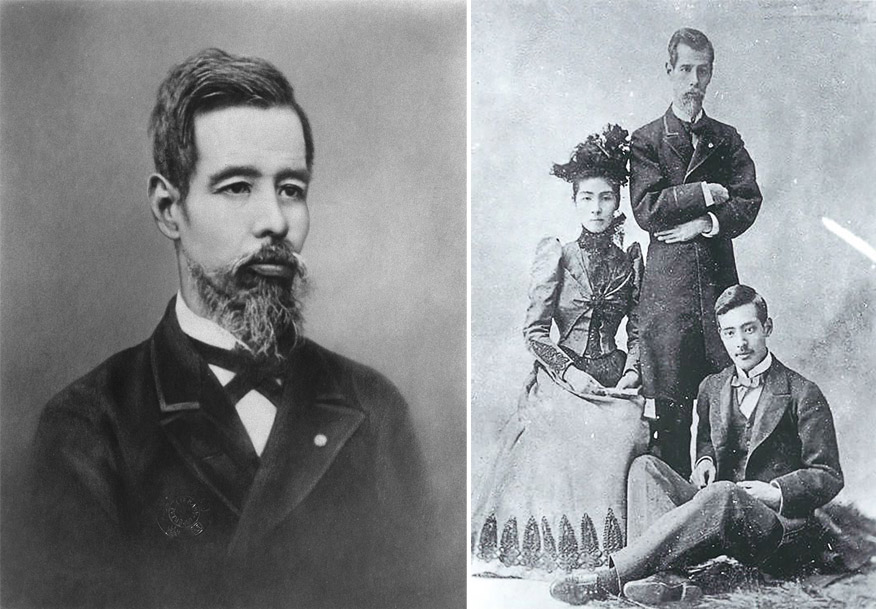

The correct answer is — Mutsu Munemitsu. Now, it’s unlikely you’ve ever heard of him unless you have a doctorate in East Asian studies.

Mutsu Munemitsu was a statesman and diplomat in the Meiji era and is regarded as one of the most famous foreign ministers in modern Japan. Born in 1844, an outsider in the Meiji government, he took charge of the revision of unequal treaties and most notably, he was the lead negotiator in the Treaty of Shimonoseki which ended the first Sino-Japanese war. Among other terms, the treaty forced China to give up much of its territory, including the island of Formosa (today’s Taiwan).

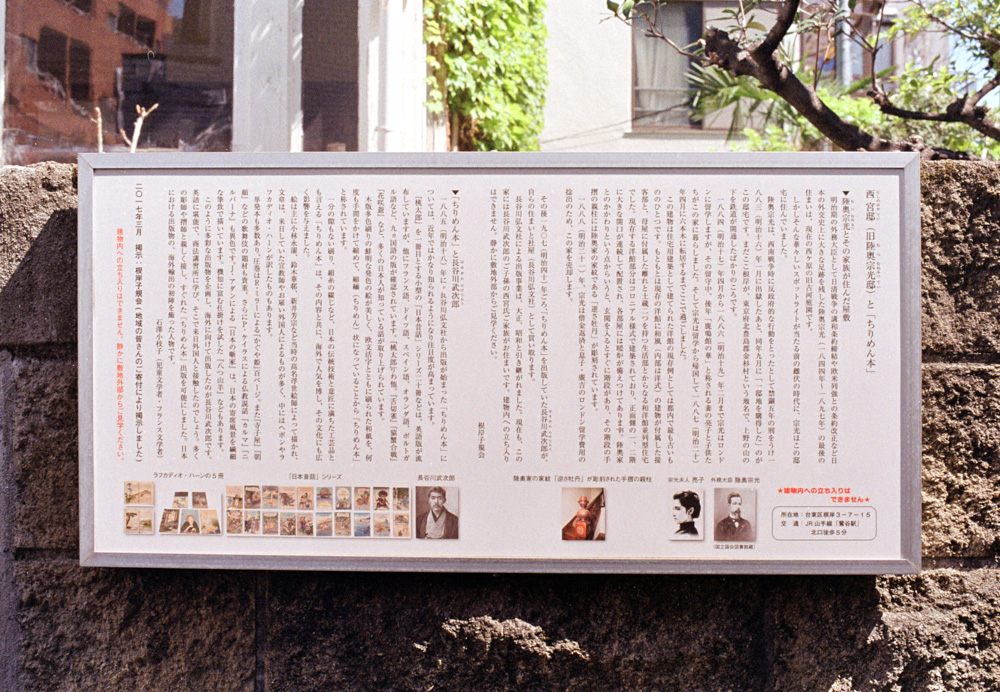

The house we are visiting today was Mutsu’s residence for 4 years between 1883 and 1887, the time before he became active as a diplomat and foreign minister. He bought this property just after he was released from prison in 1883, where he was sent because of his antigovernmental involvement in the Satsuma Rebellion. However, he himself spent only a short time here. Between the years 1884 and 1886, he studied abroad in London, while his family stayed in this house. As such, not many people know about this place but for those who do stop by in this neighborhood, there is information written on a board in front of the house.

A few years later, Mutsu went on to build a new home, a large mansion, located in what is now the much more famous Kyu-Furukawa Gardens in Tokyo.

Mutsu died in 1897 from tuberculosis. After his death, our little colonial house was acquired by a book publisher Hasegawa Takejiro who is known for publishing a series of woodblock-illustrated books introducing Japanese folk tales to foreigners. Today, the house is owned by the descendants of Hasegawa who use it as a place to live and work.

I think it is quite a miracle that this wooden house survived in its original form for nearly 140 years, considering all the disasters that could have destroyed it, like fires, or the massive bombings of World War II, or natural disasters such as earthquakes.

![[Photos] Autumn Colors at Kotokuji Temple](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fsgp1.vultrobjects.com%2Fpfj-static%2F2025%2F11%2FIutHLn2g-02.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![[Site Update] Goshuin Collection](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fsgp1.vultrobjects.com%2Fpfj-static%2F2025%2F11%2FIMG_3251.webp&w=3840&q=75)